1921

Treaty 11

The Canadian government was unenthusiastic about extending Treaty rights north of the 60th parallel beyond the Treaty 8 boundaries. The chief accountant noted that in 1910 there were no funds for any treaty negotiations or promises. It was noted that the Dene in the north country were looking for an agreement that would put them on equal footing with their Treaty 8 friends and relatives. They were not intending to give up their land but wanted access to the services of southern Canada included in a Treaty deal. The Canadian government did not see the point of extending those services to a widely separated group of people.

That all changed in 1920 when Imperial Oil produced a working well outside of Fort Norman. With a new interest in controlling the land, Treaty Commissioner Henry A. Conroy, supported by Bishop Breynat, was sent to get the required signatures on the Ottawa-prepared Treaty 11 in 1921. Conroy was instructed to stick to the original Treaty 11 draft. “You should be guided by the terms set forth therein and …no outside promises should be made by you to the Indians” (Fumoleau, 2004).

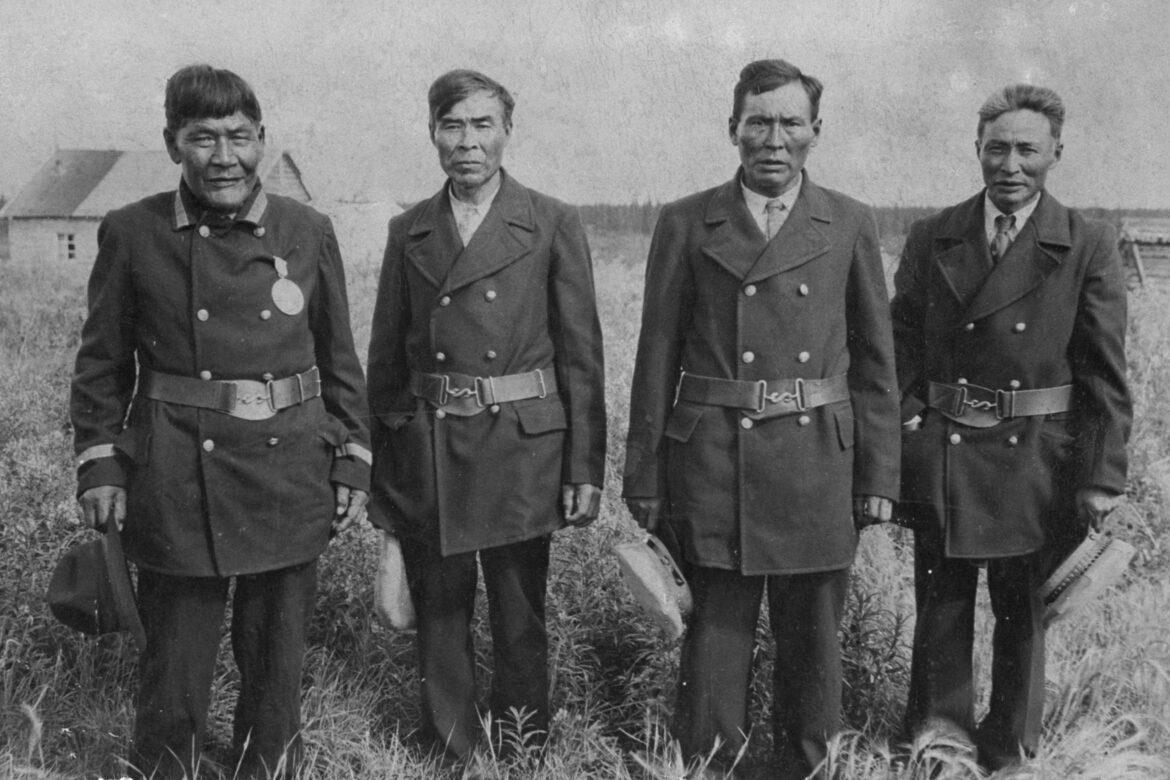

Notice was sent out in advance that a treaty party would be travelling north in the summer of 1921.The stops in Fort Providence, Fort Simpson, Wrigley (Fort Wrigley), Tulita (Fort Norman), Fort Good Hope, Tsiigehtchic (Arctic Red River), Fort McPherson, and Behchokǫ̀ (Fort Rae) produced a signed Treaty. However, the differing understandings of the government and the Indigenous people are still in dispute today. Continued land access for hunting and fishing were the principal issues for every Band negotiating with the Treaty Commission. Oral history tells of an agreement that would not change the Dene People’s relationship to the land.

When Henry A. Conroy died just a year later in 1922, he did not leave a record of any oral promises, but many of the people present remembered. The signatories at the Treaty 11 negotiations, including Bishop Breynat, fought to keep the federal government’s promises alive.

In an interview with CBC’s John Last for the 100-year celebrations of the signing of Treaty 11, Norman Yakeleya, the Dene National Chief, said: “They [had] agreed to … a peace and friendship treaty,” but the government’s text of the treaty claimed that the Indigenous peoples surrendered their land and hunting rights to Canada. According to Tłı̨chǫ history, at the time of signing Chief Monfwi said, “as long as the sun rises, the river flows, and the land does not move, we will not be restricted from our way of life.”

Treaty 11 is a complicated issue. A critical look at the process has resulted in outrage from Indigenous peoples all over the Treaty 11 territory. Modern land claims, self-government negotiations, and agreements such as the Tłı̨chǫ comprehensive land claim agreement and Délı̨nę self-government agreement, try to rectify the difficulties in the original document.