1928

Game Preserves and the Thelon Game Sanctuary

Treaties 8 and 11 promised Indigenous people access to their traditional areas and livelihoods without interference from any government. Yet, in 1916, the Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds created an enforced season for hunting. In 1917, an Act regulating Game in the Northwest Territories of Canada specified a closed season for moose, caribou, mink, muskrat, ptarmigan, wild geese, wild ducks and other like animals. The beaver season closed in 1928 as few beavers were left to trap after extensive harvesting for the fur trade. This caused serious problems for the Indigenous people in the NWT, and the Canadian Government’s unilateral actions did not consider the effects of the new rules on the people of the land nor the contradictions to the Treaties.

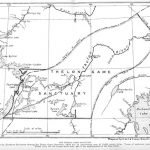

In the 1920s, non-Indigenous trappers were moving into Dene and Inuit land; with no families to support and well supplied to run long traplines; they effectively removed all fur-bearing animals from the regions they trapped. Airplanes helped these trappers access distant areas. By 1923, when once plentiful muskrats could not be found, even government officials suggested creating game preserves for Indigenous use only. That year the first game preserves were established. In 1928, the largest muskox zone in the Thelon River system was also created. Access for local Indigenous hunters was considered, but ultimately, the Thelon Game Sanctuary was functionally closed for all people to protect the muskox herds.

In 1928 William Hoare, the first Thelon Game Sanctuary warden, and his assistant Jack Knox of Fort Smith, built a warden’s station on the Thelon River, now known as Warden’s Grove. From there, they began to patrol the sanctuary. They chased all the Dene and Inuit from the refuge threatening jail if any were caught hunting or trapping within the Thelon boundaries.

Dene and Inuit hunted in the area for thousands of years and struggled to understand what right non-Indigenous people had to stop them from hunting on their traditional lands. Restricted access was especially difficult for Indigenous people to accept when they saw Hoare and Knox hunting in the sanctuary when their supplies began to run low.

The first wardens only remained in the Thelon Game Sanctuary for two years. The report Hoare prepared for the Government made particular reference to the concerns of the Dene and their traditional hunting areas. The Thelon Game Sanctuary was ultimately reduced in size, and the Dene were able to resume hunting caribou, but not muskox, in much of their traditional territory.

Hoare’s report raised awareness of the plight of the muskox. Herd sizes slowly began to increase, but the economic condition of Dene and Inuit hunters in the area remained precarious. The next decade was a time of desperation.