1962

Regina v. Sikyea

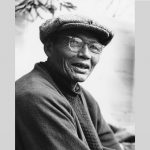

In 1962, Michel Sikyea was a 61-year-old Dene hunter. Michel was orphaned when he was three and grew up at the Fort Resolution Roman Catholic mission. He spent most of his life trapping, hunting and fishing at Moose Bay southeast of Yellowknife, occasionally working at Con and Giant mines. On May 7th, 1962, he shot a female mallard duck for food at a small lake outside Yellowknife. What would follow that small act was a pivotal court case and public awareness and recognition of Indigenous claims for self-determination and self-government. His ‘Million Dollar Duck’, at the centre of the case, became a symbol of Indigenous rights.

The RCMP charged Michel Sikyea with hunting out of season, a charge he did not deny. He told the police officer that it was a Dene treaty right to hunt anywhere. Sikyea was charged with contravening the Migratory Birds Convention Act and appeared in Justice of the Peace Court in Yellowknife that very same day. He pleaded guilty and was fined $10 plus $4 in court costs. This seemingly simple case could have ended then had it not been for Judge John Sissons. He heard that a Justice of the Peace fined Sikyea for this infraction and urged lawyer Elizabeth Hagel to file an appeal on Sikyea’s behalf. The appeal was granted, and in November of 1962, the case went to court with Judge Sissons presiding.

Evidence brought forward during this trial included that Michel Sikyea was a witness to changes made to Treaty 8 at Fort Resolution in 1923. He told the court that at that time, he heard the government representatives promise that the Dene would always be able to keep their traditional hunting, fishing, and trapping rights.

Arguments were made concerning these rights and whether they took precedence over modern laws. Sissons’ judgment stated that the Migratory Birds Convention Act did not apply to Indigenous peoples. The NWT court decision was appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, which sidestepped the issue of the legality of the Migratory Birds Convention Act and declared that the duck, claimed by the defence to be tame, was, in fact, a wild duck and that Michel Sikyea was therefore guilty of hunting out of season.

Michel Sikyea, through his lawyers, then petitioned the Exchequer Court of Canada for compensation for all Indigenous peoples for this Supreme Court decision. His lawyers asked that since treaties had been broken and Indigenous peoples were no longer allowed to conduct spring hunts, either all the lands ceded to Canada under these treaties be returned to Indigenous peoples or that the people should receive compensation.

Even though this petition to the Exchequer Court went nowhere, it eventually resulted in a growing call for the recognition of Indigenous rights and Treaty violations. Many years passed before Canada legally recognized Indigenous rights in the Constitution Act of 1982, which launched the modern land claims process. The duck, which had been stuffed, became known as the ‘million-dollar duck’ because of the million dollars in court cost related to the $1 dollar fine and spent many years sitting on the top of a bookcase in Judge Sissons’s office. Now, along with an extensive collection of Inuit art representing various court cases that forms part of the Sissons Morrow Collection at the Northwest Territories Court in Yellowknife.

Michel Sikyea and his wife Rose had 12 children, and he was a councillor in Ndilo for many years. Michel Sikyea died in 2002 at the age of 102.