1969

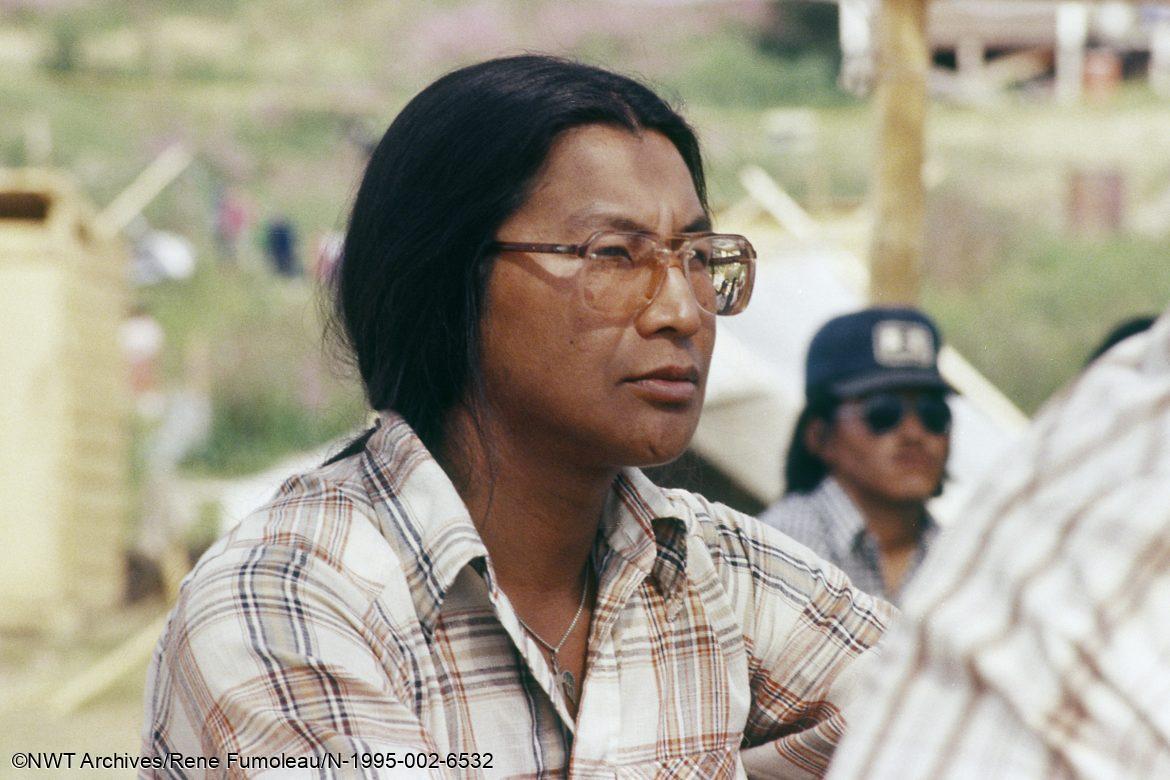

The Rise of Indigenous Political Organizations

Economic and political events in 1969 spurred the beginnings of several influential Indigenous political organizations. Southern corporations were moving north in ever-increasing numbers to explore and exploit mineral, oil, and gas resources in the Mackenzie River Valley, Beaufort Sea, and the Arctic Islands, thus disrupting the traditional Indigenous harvest. Meanwhile, the Canadian Government proposed the controversial ‘White Paper’ intended to dissolve the Indian Act, dismantle its Department of Indian Affairs and end special legal protections for Indigenous people. The White Paper did not include consultation with Indigenous groups, which caused an uproar. In response, Indigenous people, including a new generation of young, savvy leaders across Canada, organized themselves to protect their homelands.

The creation of political groups was inspired by traditional Indigenous political structures that had been in place before the fur trade. This Indigenous revival included new organizations representing the Dene, Métis, and Inuvialuit people of the Northwest Territories. These organizations ranged from political to cultural and spiritual. In October 1969, Dene voices joined the first meetings of the NWT chapter of the Indian Brotherhood. Pierre Catholique, Chief of Łutselk’e, noted, “Never again will one chief sit down with many government people. From now on, if 21 government people show up, 21 Indian members will be there too.” The Inuit and Métis quickly saw the value of empowering their voices. The Committee of Original Peoples Entitlement (COPE) met in January 1970, gathering those who wanted to speak for all original people of the NWT. Agnes Semmler became a powerful advocate for the recognition of Indigenous rights.

The Indian Brotherhood and COPE brought issues to the territorial and federal governments, “We functioned as a group of activists with links to the eastern Arctic, the southern Mackenzie and the central Arctic. It was unusual in those days and disconcerting to the newly formed GNWT,” Nellie Cournoyea, an active COPE leader, remembered. She noted that the establishment of the Hamlet, Village, and Town governments by the GNWT was questioned by the COPE participants as the imposition of this governance structure changed the relationships of territorial settlements with their people.

The Indian Brotherhood of the NWT, COPE, and the Métis Nation (organized in 1972) actively raised concerns over treaty violations, land use issues, and human rights abuses. Although these groups often worked independently, they were all part of a growing response to advance the rights of Indigenous people in the NWT and Canada.