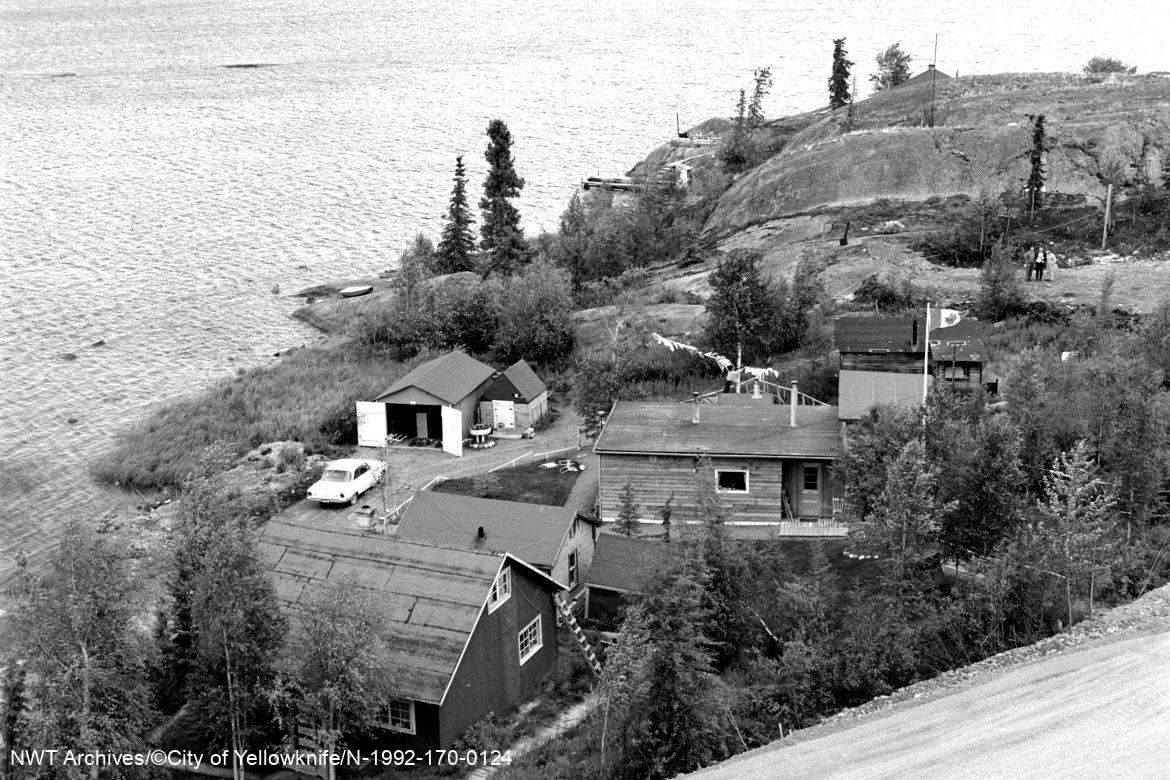

1968

Métis Community on School Draw

Yellowknife, in the 1940s and 1950s, was a magnet for northern people looking for work in the gold mines. Many Métis started to move into the community to take advantage of the opportunities. Métis, Dene and white settler families began to gather along the shores of Yellowknife Bay in an area now called School Draw Avenue, named after a public school that operated in the small gully known as a draw from 1940 to 1947. The families purchased existing homes or carved out a space to build amongst the rocks and trees near the shoreline nestled between the two significant mine developments to the south (the Con and Negus Mines) and north (the Giant Mine complex). The Yellowknife children went to the local school built overlooking the lake. The community of School Draw developed nearby with proximity to good fishing and berry fields.

The declaration of Yellowknife as the territorial capital in 1967 threatened the permanence of the School Draw neighbourhood. New government workers needed homes, and the non-Indigenous settlers had their eyes on the shoreline, lake, and island homesteads. The School Draw area had never been surveyed as it was caught in a complicated tri-party ownership conundrum mixing Federal Crown, town, and territorial land rights, without any regard to pre-existing Indigenous title or established homes with gardens and fences. In 1967 the city took action ahead of any agreements by plowing roads and damaging properties. Sewer and water lines were placed to accommodate a 45-lot Government worker housing scheme. People gathered to voice their concerns in July 1968 when it became apparent that Yellowknife land planners had no intention of considering their interests.

The City of Yellowknife finally gave a proposal to its residents in August of 1968. Option one was to buy the land they were on now and build a new home up to the town’s regulations, which included connecting the home to water and sewage. Option two was for them to leave and have the town purchase the lots and sell them to other residents who will then build a house up to the same standard. If the residents chose to leave, they would be offered public housing at rents geared to their income. Option three was to have their home, at the city’s expense, moved to another lot on School Draw, but not where the city was surveying. The price per lot was set to $3,100 by the city. The residents had ten days to decide what to do following the proposition of these options.

Several residents of School Draw were upset to learn that the houses they lived in would either be torn down or moved if they did not make a $3,100 purchase. Many of them believed it was unfair, so a group of them hired a lawyer from Edmonton. It came to light that many of the School Draw residents had made numerous attempts to purchase their lots in previous years and had been denied by the city. Not only that, but the lots in previous years were sold for less than $500 (some were sold for $75 each), making the $3,100 a substantial price increase. With the lawyer involved, the residents negotiated a fairer price per lot of $500. Michel Sikyea, a Dene man famous for his Million Dollar Duck and the earlier legal battle over Indigenous hunting rights, argued, “I have a perfect right to this land; I got here before any white man was here.”

The belief within the Métis community was that their families were targeted for removal. They had significant concerns over the refusal to survey existing lots. Moving away from their long-existing neighbourhoods untethered the Métis families, and the survival of the Métis community has been a constant struggle.

In the end, 45 government houses were built, and today School Draw Avenue is a major subdivision of Yellowknife.